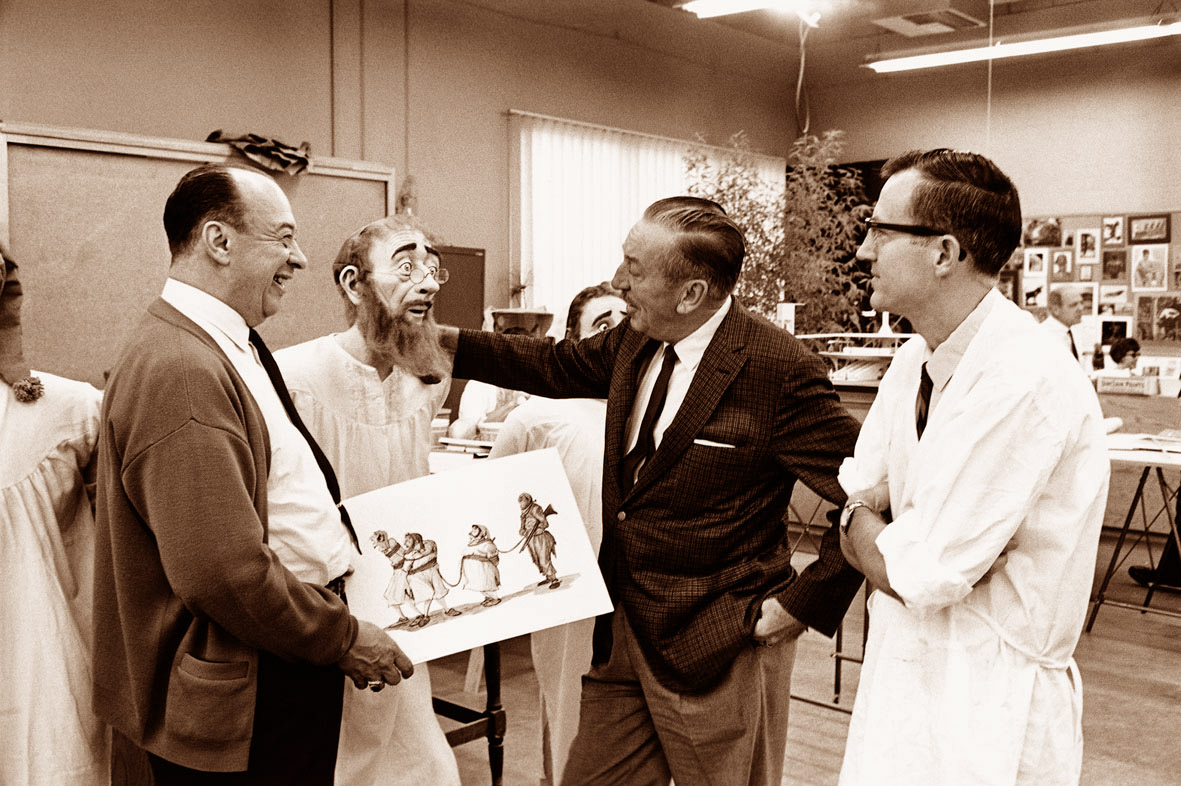

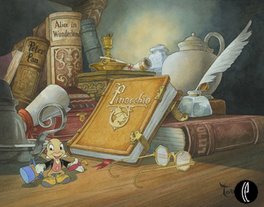

Legendary WDI Imagineer and sculptor Blaine Gibson passed away last Sunday and thanks to my co-author and good friend Didier Ghez i post today this great interview of Blaine Gibson. As long as the interview below might look it is just an excerpt from the full interview that Didier Ghez did of Blaine Gibson on January 28, 2008. You'll read below only the excerpts related to his career at WED Enterprises, now Walt Disney Imagineering, but you have to know that before entering WED Blaine Gibson worked at the Disney Studios as animator and sculptor.

Didier

Ghez: When and where you born? I think it was in Rocky Ford, Colorado on

February 11, 1918. Is that correct?

Blaine Gibson: That’s right.

DG:

When did you become interested in art?

BG: As long as I can remember…I became

interested in art when I was living on a farm four miles from Rocky Ford,

Colorado. A child gets bored at four or five, so I did things to entertain

myself as a child, before I was able to get out and help in the fields. My

mother was a very kind and generous lady and would kind of watch what I would

do. That was actually encouragement from my viewpoint. And she would let me

take the newspaper and pick up the barber scissors, which are the only kind of

scissors I had, and I would cut out silhouettes of the various animals around

the farm—that would be pigs and cows and horses and even birds, and rabbits

that I would see running through the yard. And she would actually pick up a lot

of my mess, but she would save the little animals just so that they would be

separate. I have no idea how good they were.

But anyway, that was the wintertime and

then when the summer came we did not have enough water on our farm to sustain

farming without irrigation. We had perhaps in some years twelve to eighteen

inches of rain, but that was not enough. So my dad irrigated and I discovered

this wonderful waste ditch. When the water finally evaporated, it made the

greatest mud in the world. I found I could make all kinds of little things. I

didn’t make pots or little dishes or pancakes or pretend that I was a cook or

something like girls seem to do. But I would make little animals, little

rabbits and pigs and animals lying down, because I discovered early on that the

legs were an inhibiter. So I would actually do these little things and set them

up on the porch, which my mother soon corrected me on because she did not want

to get them crushed all over the porch when they dried. So I had to move them

all over to the side and let them dry and leave a path for people to get

through over the porch to the house. That was my early start in art. And

strangely enough, it continued on into my vocation in a similar but more

sophisticated way. I became an animator and I was an animator for 20 years. And

I was the lead sculptor for 23 years after that, because I was doing sculpture

on my own time while I was an animator.

DG: A bit later on in your career at Disney you moved into Effects Animation. Why?

BG: When World War II came, Disney was

taken over by all the military services. It was all there was. We did training

films for all the services. Effects Animation was the best medium to use for

these films, so that's what I worked on. I could have been sent back to

Virginia where they had a place that did military training films, but Disney

did them right there in Burbank, so that's where I worked

DG:

And that’s the time you worked in Effects?

BG: That’s when I went into Effects, and I

stayed there for ten years because I was married and I had a job. Effects were

not un-interesting, but I felt not nearly as interesting as character animation,

which I really wanted to do. I was doing character to start with. As I

mentioned before, I was an assistant animator on character animation with Ken

Hultgren before the War. Ultimately, I decided that I did not want to stay in

Effects Animation, so I went to Ken Peterson, who was the head [of Animation] and

he said, “You’re in luck, Frank Thomas is looking for an assistant.” I thought,

“Good grief, even though I am a full-fledged animator and have been for ten

years, I’m going to be an assistant again!” But I took a cut in my weekly

salary so I could go work with Frank. He devoted many hours of time working

with me and made sure I wouldn’t be doing the things that would be regularly

required of other assistants, which is just cleaning up the animator’s drawing

and making it so it can be made inkable. Then he started giving me animation. I’d

get something else with a little more personality and I was really enjoying

myself at that time.

But I was also a sculptor, so I made the

"mistake" of showing some of my sculptures throughout the years when

I was a young man in my 20s and 30s. I would show these sculptures in the Studio

library and Walt didn’t forget anything when he saw it; and that’s where my

downfall came. Walt got the idea for Disneyland. It grew from a small idea, a small

location across from the Studio to a rather large organization down at Anaheim.

And from then on it was a case where in the early 1950s Walt had me start doing

things, which were in line with ideas he had about his theme park. And they

were all sculpture. But I also loved animation, because Frank did everything he

could to help me become a good animator.

DG:

What were the challenges of Effects Animation?

BG: Some of the ocean water in Pinocchio with Monstro the Whale was

great and was very challenging for me to do in line. And while there were

people who were quite happy spending a life with Effects Animation, that was

not for me. I had done some personal tests as a young man that indicated to me that

to make a character come to life and give it personality was a far bigger goal

than making a tree blow or leaves fall or smoke going up or fire. I like to

have something with a face on it, even an animal. Animals were fascinating and,

especially when Walt did a picture like Bambi,

I thought the work that they did, the life… There again I come back to my old

friend and mentor Frank, and to Ollie Johnston… to their work on Bambi. Mostly little things, like

Thumper on ice and Bambi on ice. That’s the most beautiful animation I have ever

seen or ever will see… where Frank made Bambi look like a clumsy little

ungulate as opposed to the little rabbit that could get on the ice and slip

around and never hurt himself. Bambi was like an animal born on stilts on ice. It

was a great, great piece of work.

DG:

What was the first sculpture you did for Disneyland? Was it that of the Indian

chief head?

BG: I did many, many sculptures for

Disneyland. For the Indian Village I did the heads and Herb Ryman and I painted

them. For the bodies, interestingly, they actually cast a man named Willie

Strode who was an athlete. There again, we all have to learn sometimes. Experience

is the key. They want to get it done and so they’d have a guy lying down and

cast him lying down. Well, that’s as stiff as a board. You want to be careful

not to get things too stiff. You’ve got to get it more natural. But that takes

time and sort of a history of discovery and trial and error, in other words. But

it should always be done with as much critical analysis as possible.

DG:

So the first sculptures you did for Disneyland were those of the Indians?

BG: The first sculptures were when I was in

animation, with Frank Thomas; they were the Sleeping

Beauty characters. And then I think I did another one for somebody, a seal

or something, I don’t remember what it was.

DG:

For animation?

BG: No, it was just a study of a seal for

something. Maybe it was something we never even used. But we did a submarine

ride early on where I did mermaids for Disneyland. We ran into problems,

because there were a lot of unknowns, and one of them is that the chlorine in

the water and the compatibility of the materials we used sometimes didn’t jive.

Those things did not hold up because of the chemical incompatibility. We didn’t

know those things when we started.

DG:

Let me jump in time a little bit. In Pirates

of the Caribbean, some of the figures were based on Marc Davis’ sketches …

BG: The storytelling device of having these

ransacking pirates was his idea, but my job was to turn it into

three-dimensional compatible designs. So I actually did the heads quite

separate from what he did, by just knowing the kind of characters we had to

have. I was not fighting Marc and he was not fighting me in any sense. We were

going in two different directions. It’s like the story sketch in an animated

picture would be what Marc was doing, and what I would be doing would be to

crystallize the character. I happened to do that in my own way, because Walt

and I worked together on that. The thing that I wanted was to have real people,

not cartoons that were brought up to life size. So my job was to make it so

that they would be credible. Walt wanted the ride's characters to be

believable. If you just made a little cartoon… sure, you could tell a story

with a little cartoon… I’m not faulting Marc at all, he’s one of the greatest. But

he did have this ability to draw a cartoon that would be funny and maybe have a

mouth which, when fully analyzed, would be six inches across. And it can’t work

in three dimensions and be compatible. So I had to base my character from the

inside out. They were based on real people and so that is what I insisted on.

DG:

There’s a rumor that you based some of those characters on people from your

church.

BG: It’s just that I did not exclude any

place for analyzing human types, and I have a whole series of drawings that I’m

going to exhibit here to illustrate that. They’re just simple line drawings of

showing ways of keeping things in a range. They were suggestions I had left for

other artists that might inherit my problems of trying to develop characters

for shows. I not only worked on Pirates

to develop those characters, but even on a whole series of characters for the American Adventure pavilion, which

actually has whole sets of characters that have to be like people.

DG:

So then there is something to that rumor that some of them were based on people

you would observe at church for example?

BG: Absolutely, yes. My wife would say,

“Blaine, you’re staring at that person.” She’d sort of kick me. [Laughs] That

was embarrassing her a little bit, me staring at somebody, and I was really

giving him the once over, you know. Yes, that did happen in church, and also in

restaurants.

DG:

Chris Mueller was also…

DG:

Chris Mueller was also…

BG: Chris Mueller? He was by far the best

of our ornamental sculptors. I never tampered with his ornamental work. When he

started doing heads and things like that, I would come in and work on those. But

as far as the traditional ornamental sculptures of pillars, Corinthian and

Doric and Ionic and all that sort of thing, this man knew it all. I’d be crazy

to get in there and criticize something in that area. I admired him. For 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Chris

Mueller actually did that wonderful squid. I brought in books for Disney to use

called Wonders of Animal Life, which had

records of how big the giant squid got. I remember Walt came in and said,

“What’s the biggest size squid according to your book Blaine?” I said, “It’s

actually 60 feet, Walt.” He said, “We found a book where it’s 80 feet. I’m

gonna use that one.” So that’s the length Chris Mueller used for the squid.

DG:

What type of person was Chris Mueller?

BG: I didn’t work with him very much, but I

would say he was a fine gentleman. I would not hesitate to give him anything in

the monumental or ornamental line of architectural sculpture. I would say he

was the best. I’m not a great judge of that because I don’t even consider

myself good at it. But I think, at least in my opinion, he’d be right up there

with the best.

DG:

What about Jack Ferges? What kind of artist was he and what were his

specialties? Any special memories of him?

BG: Jack Ferges was my assistant for a

while. A very amusing guy. He was six foot seven or eight, weighed two hundred

and eighty pounds at least and was a former football player with a great sense

of humor. At first we had one big table, because we were really moving from

Disney’s studio to Glendale where Walt was setting up his place. Jack was with

me at that time and was going to be my assistant, but we ran into some

complexities because we had to have a union system for the sculptors that I

used, because we were going to use a whole team of people. Jack belonged to the

animators’ union, not the sculptors’ union. I did belong to it, because some

time before I had to join it. Jack had an ability to make miniature models. Walt

would come in and see these tiny little things he was able to make, little

model sculptures or building sculptures, or something else. Rolly [Crump] said

to Walt, “You know he can’t do that with his big hands. When you’re gone he has

a pair of little hands that he gets out of the drawer. He uses those to do his

tiny work.” (Just kidding Walt of course.) It did look like he couldn’t do it

with his big hands because he was a football player. He did have huge hands but

was a very talented guy.

DG:

You said that he had a great sense of humor. Do you remember any pranks?

BG: If I went to the bathroom, he’d take

all of my junk and shove it back on my side. When he went to the bathroom I

would shove it all back again. It was just a big pile of stuff. It was sort of

a humorous thing. He was always making jokes and a funny guy with a different

kind of humor. Everybody liked him.

Early on the sculptors and I were all

together in a great big room. Later on I moved to our big separate studio. But

this was sort of a model shop. I remember we would have to move complete models

up on the deck in storage and we would all be lifting, and then all of a sudden

we would notice it just left us. And here Jack was being so tall, six foot

eight, he’d keep pushing it on up. It would just disappear… he’d lift it clear

over our heads… the whole thing.

DG: You

did some of the sculptures for the updating of the Jungle Cruise. Can you tell me the story of Walt pulling down his

pants to act out a part of an elephant climbing up a bank?

BG: Oh, that was afterwards. Most of the

ideas that we used earlier on were ideas that Marc Davis came up with, humorous

ideas that showed a bunch of happy elephants sitting and bathing in the waterfall

and that sort of thing. But Walt came in and saw those I had designed as a

scale model for later use, which we had made in plaster and then we would cut

them off at different lengths so that they would look like they were in a pool,

and Walt said, “In our nature pictures we have one elephant climbing out on a

bank and he’s reaching his trunk up to reach a limb and bring it down. And he’s

in the water, but he’s got one knee on the bank.” So Walt kind of pushed his

pants down a little, got a chair; his arm became a trunk and he had one arm on

the back of the chair which would have been the bank. And then he raised his

right knee up on the chair and his arm was raised with his wrist bent, and he raised

it up to grab a branch (like the elephant in the Disney True-Life Adventure)

and said, “Can we do that?” I got the picture right away of what scene he was

thinking of. So I went home and did that model. We did it full size for

Disneyland.

DG:

Do you have other stories of meetings with Walt or working with Walt?

BG: It would take too long to think about

all of them. Walt was very involved in our projects . . . He had an idea for

the Hall of Presidents before we

actually did it. He was there a lot when I was working on Lincoln in the

beginning. He knew that I was making every effort to be authentic about it, so

I went to him about acquiring things through our studio-props department. I had

them buy a mask from Kathryn Stuberg, who had a wax museum in Hollywood as I

remember. I wondered if the Studio could buy it. (When I went to see Kathryn

Stuberg one time I started to ask her a lot of questions. Of course I was quite

a young guy in her view, I guess. She said, “Why should I answer you?” or “Why

should I do this, you might be just going right out and creating a Wax Museum?”)

But I was able to get our Props Shop, who would have been less suspicious, to

go down there and they actually bought this mask of Abraham Lincoln. So I went

to Walt and showed it to him and he said, “Yeah, that's a great idea.” Later,

he was doing one of his TV programs and he was struggling with what I had told

him about the mask and he said, “Who was it that did this mask?” And I said, “The

guy’s name was Leonard Volk and he was a Chicago sculptor in 1860 and did this

mask from life.” He forgot it, and then said, “You get up here, Blaine.” So I

had to get up with him for the cameras and tell him about this story of getting

this mask of Abraham Lincoln.

DG: You

worked with Ken Anderson…

BG: Yes. Not enough good things can be said

about Ken.

DG:

How difficult was it to translate Ken’s sketches to 3D?

BG: Remember I was an animator for a long

time and all characters that we did were composites of contributions of many

people, so I was used to that. That must be one of the characteristics of an

animator, to make every effort to use what was best that was presented in

describing a character. Ken Anderson was capable of originating characters for

animation and strangely enough he never became an animator. But he was an

excellent character developer and storyman and perhaps one of the best layout

artists that we ever had. He had a background in architecture. That was a great

asset, as it was for Claude Coats, who also had a background in architecture.

Ken’s talent, however, was much more toward character than Claude’s. He would

come up with very interesting character concepts.

DG:

On what specific projects did you work with Ken?

BG: I worked with Ken on things like Skull

Rock for Disneyland. I also worked with him on pictures, because he was what we

called “a layout man,” somebody responsible for much of the architecture and

the settings for the characters in the pictures we did.

DG:

You said that Ken sketched the devil at the end of the Mr. Toad ride and that

you had to do some adjustments. Why was that?

BG: It’s just that there is two-dimensional

design and there is three-dimensional design, and I awkwardly stated that. What

he did were little devil characters, which were perfectly inspirational for me

to get them into three dimensions. And that’s probably what I should have said.

DG:

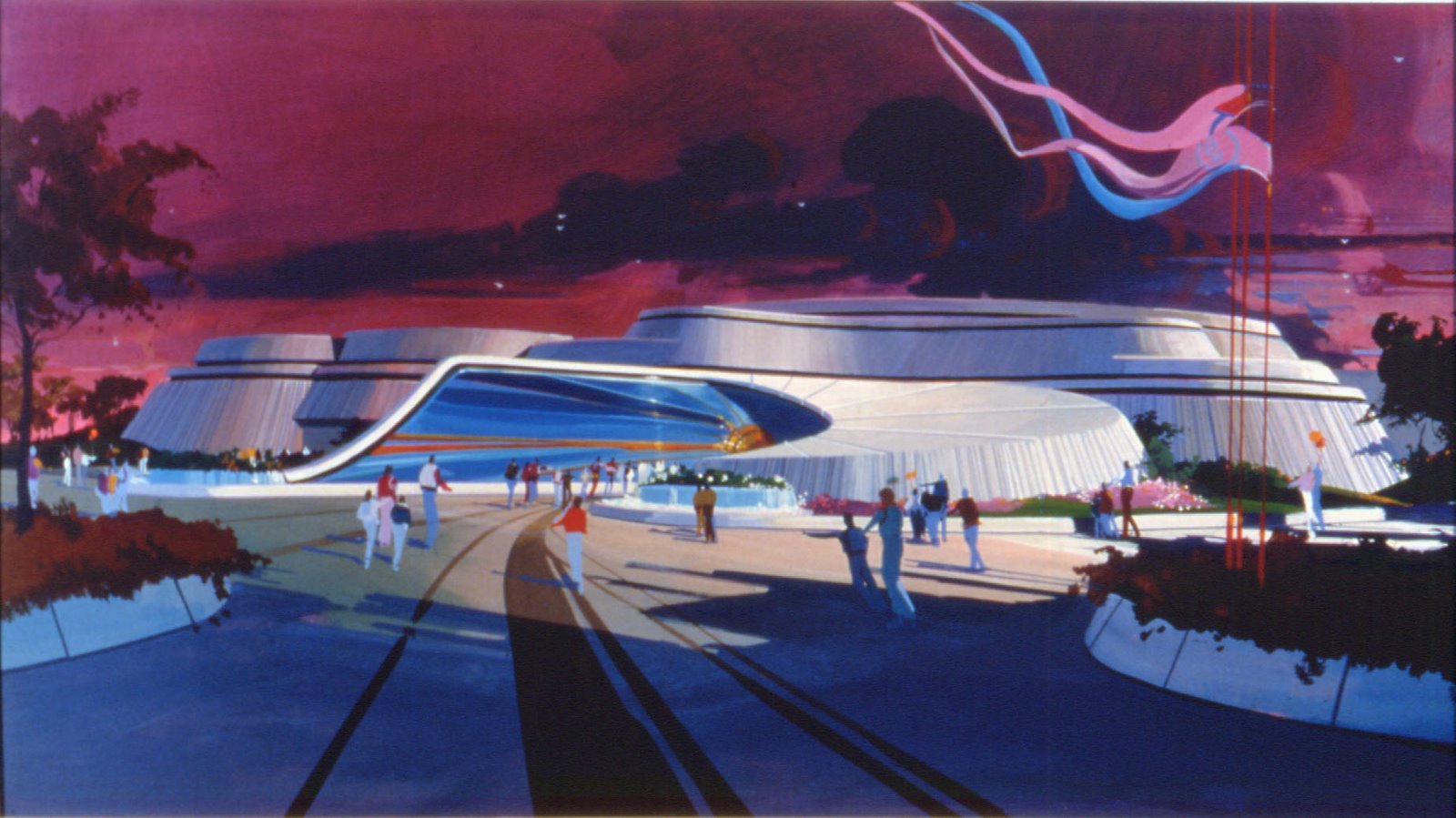

What did you think of Mary Blair as a person and as an artist?

BG: She was a wonderful lady. I only got to

know her rather late at a time when she was doing the tile decorations for

Tomorrowland. It’s probably all gone now. On occasions I had worked with her on

some special assignments, like going to a chemical company which we went to

visit together to get some ideas. She was a marvelous lady, very uniquely

talented. She had so much to do with the design elements of Small World. It was sort of difficult

for me to try and develop the three-dimensional character designs to fit her

two-dimensional style, but ultimately I think we were able to get the feeling

of it.

DG:

In the interview with The E-Ticket

you said that you did not really want to move to WED. Why? And at the time did you

do both animation and work for WED in parallel?

BG: [Laughs] I was doing sculpture on a

continual basis on my own and I was doing animation at the Studio and working

with Frank Thomas and I got more challenging animation all the time. By

“challenging,” I mean if you were an actor you would say “better parts,” work

that was more stimulating. To me animation was about as great a high as anyone

could achieve, something very gratifying when you can bring a character to

life. So to leave that would be leaving something that was pretty rewarding,

and that’s the direction I was headed.

But when I was at WED, it was different. I

was with Walt, much more than at the Studio. He was a very stimulating man.

Everybody sensed that in our interactions at WED. Whereas, when we were

animating, we would go in a sweatbox or a projection booth, a little theater,

and Walt would sit at the back of the room and the scenes would go by that we

were working on at that time… take for example 101 Dalmatians. Walt would say, “That’s coming well, that’s coming

well,” then move on and not make much comment on it. And that was a good

position to be in. If he said the famous, “I think that needs work,” that would

give you a little pause.

At WED, I often found myself working with

Walt and he was sitting on a chair right beside me, discussing what I was

doing. And that became quite gratifying too, because the man had this ability

to really stimulate activity and thought and make it a team project, which we

were all very interested in.

DG:

Was there a time that you were both doing some sculptures for the parks and, in

parallel to that, working in animation?

BG: Yes. That’s a good point. There was an

overlap of time that I was doing sculpture down at Disneyland, and then having

to animate a scene at my desk after that.

DG:

You were talking about Walt’s ideas for The

Hall of Presidents that was opened after Walt’s death. Did they consult you

recently about the sculpture of Obama?

BG: Valerie Edwards, who took my place, did

the Obama sculpture. She is very competent and more knowledgeable on the

anatomical detail of the human being than I am. I did go in and I checked on

what she was doing and made a comment or two, but the head was done well. If

two artists approach a portrait, they will do it differently and you have to

acknowledge that.

DG:

On Carousel of Progress, who did the

paintings of the figures? I understand that you did some painting and Harriet

Burns did some painting, is that correct?

BG: For many characters that I worked on with

Harriet, like in Small World, I would

do the sculpture and design and Harriet would do the painting. Alice Davis did

the costumes on that one. But on the Carousel

of Progress there was a man named Preston Hanson who was actually a rather

popular TV star at that time. He was one that Walt had hired individually and

had me sculpt his head and figure and all that sort of thing along with all the

other characters in the show. We had a makeup man, who had come to Disney. He

made a cast of Preston Hanson for me so I’d have something to start with. I

remember one of the guys, Bob Sewell, who was head of the Model Shop at that

time, said, “Boy, that’s not gonna work,” because I was changing what this

plaster cast was. Then one day Preston came in and sat for me while I finished

the sculpture and Bob said, “Now I see why you changed it.” What happens is

when you take a cast of a person using a soft plastic material, gravity will

push the flesh away from the bones enough to distort it. I would have to change

it back to "normal." Bob Sewell noticed afterwards. He could see why

I changed it.

DG:

Tell me about the bust you made of Walt in the sixties? What made you decide to

make it?

BG: It was suggested by Dick Irvine who was

president of WED Enterprises at that time. He said, “We want you to do that

while you’re working with him all the time.” So I did it. I knew Lillian Disney

didn’t like it very well. She didn’t tell me that, but I knew that she was not

happy with it. I still have that head. I started to destroy it. Then I called

the heads of Retlaw, the people that managed all the Disney properties, who had

a bronze cast of the bust, and I said, “I’m going to destroy this head I had,

but only on the condition that you destroy the bust that you have.” And they

wouldn’t destroy it. [Laughs] So it is still there somewhere and it has a bad

patina, partly because of time. Bronze is subject to more bad things in L.A.

than probably many places in the world, because of the sulfuric acid, which is

a very strong oxidizer. Bronze responds very much to sulfuric acid and it gets

black or green depending on what the elements are.

DG:

Where were you when Walt passed away?

BG: I was at Imagineering and it was very

definitely a sad time. It was getting close to Christmas, but it was not a

happy time. I was actually doing a project for Walt and I have a copy of that

here. He came in one day and he brought a sketch that somebody had made of this

idea. He said, “Would you please do this in three-dimension? Debbie Reynolds

and her husband and Lilly and I…” I believe it was bridge he said they played

together. He wondered if we could do a project for Debbie Reynolds, because at

that time she was the president of Thaliana Society, a group of actors and

actresses that got together and did services for groups of children that had

learning difficulties of one kind or another. The one that provided the most

services for these children would be given an award, and it was going to be

Goofy. I have a copy of it here. Basically, it is Goofy holding masks of the

two extremes of sadness and happiness… tragedy and comedy . . . with a caduceus

symbol on his vest.

DG:

In 3D?

BG: That was the last thing that I did for

Walt. I had no idea that Walt was actually dying.

DG:

That last project you did, that was in 3D?

BG: It was a sculpture of my version of

this little sketch idea that somebody in Disney’s Art Department had come up

with. I did it my own way, because I also worked on Goofy sometimes when I was

doing assistant animation.

DG:

Did you ever work on projects that were never completed?

BG: Yes, I did. Jack Ferges, my assistant,

and I did a bunch of little characters that were from the books of Oz. Walt bought

up some Oz books. Not The Wizard of Oz.

That had been taken and done beautifully in a motion picture. He bought up some

other books, and so our job was to interpret some things into three dimensions,

suggested by a man named Joe Rinaldi, who was a good sketch artist and a storyman.

And so Jack and I would interpret these. Walt really liked them, but they never

were done other than just the samples we did in three dimensions.

DG:

What was Roy O. Disney like?

BG: He reminded me of the farmers that I

knew, like my dad and others. Very genuine and down-to-earth… somebody who had

no phoniness to him. He was totally who he was. A very remarkable man and a

very fortunate coincidence that two brothers would be together like that.

I remember one time I ended up working on a

medallion of Walt that the U.S. Congress had commissioned the Disney company to

do, so Congress could present a gold medallion to Lillian Disney in remembrance

of her husband. Someone else had done a design and Lillian had become almost

angry when she saw it, commenting “Why would they have him smile and show his

teeth?” You can do it if it is done right, but the earlier design wasn’t done

right. Now, I had to be involved because Dick Irvine said to me, “Blaine, it’s

in your lap. You’ve got to do it now, and Lillian does not want him to have the

teeth showing.” I said I would do the best I could without Walt’s teeth showing.

In some of his famous portraits he had a very broad smile and I thought, “Oh

boy. Now I’ve got to make it without…” So I did this bas relief model with the

best smiling expression I could get without Walt having his mouth open, and Roy

came up to check it out. He said he liked it, so I felt much more confident

about showing it to Lillian, and she liked it too and okayed it. Dick Irvine

and John Hench all passed on it and that was the medallion that was presented

to Lillian in gold. Later it was sold in bronze as a small fundraiser for CalArts,

one of Walt's favorite philanthropies.

DG:

Speaking of Roy O. Disney, you also obviously did the statue of him for Walt

Disney World.

BG: Yes.

DG:

What’s the story behind that and why is there Minnie Mouse on his side?

BG: The story evolved from a picture that

Roy Jr., whom I knew and admired, told me was his dad’s favorite picture. Roy

was the one responsible for Walt Disney World getting opened. After the Magic

Kingdom [in Florida] was finished, Roy, his son, had apparently arranged to

have a photograph of his dad sitting on a bench with Mickey, the costume

character. But the head of Mickey was enormous. So I started making sketches. The

way I picked the size was the precedent that had been set in Fantasia of Mickey Mouse walking up to

Stokowski and shaking his hand. That was my precedent for a size. It made it

much more compatible. And also John Hench came up with the idea, “We’re not a

gender-biased company, we’re not against girls. Why don’t we have a Minnie

Mouse sitting next to Roy instead of a Mickey Mouse? You already have a Mickey

Mouse out there with Walt holding his hand and so why don’t we have Minnie

Mouse?” So it ended up that I used a Minnie Mouse sitting next to Roy with him

looking down admirably at her, and she looking up admirably to him. I think it

came off pretty well.

DG:

By the way, in the Walt statue with Mickey, why is he pointing the way he is?

BG: I was asked that early on. The thought

that came to me immediately was of Walt saying, “See all of the people coming

in? See how happy they are, Mickey?” That’s what it is all about. Of course,

Mickey’s a little short guy, he can’t see over the people, so his direction is

toward Walt’s hand. Walt is the master. But if you look at Walt’s eyes, he’s

looking out at the crowd, the people coming in, but Mickey is looking up at

Walt’s hand and he’s only finally getting the idea. It made it a little better

composition in my opinion than if I had had Mickey looking away from Walt. I

wanted Mickey and Walt to be a unit. But you look at Walt’s eyes, he’s looking

at the people coming in.

DG: Why did you decide to retire in 1983?

BG: That was a misnomer, Didier; actually I

did not really retire in 1983. I did retire officially, but Walt Disney

Imagineering kept giving me assignments for the next 20+ years.

DG:

[Laughs] Okay, so what have you been doing since you retired to Santa Barbara

in 2004?

BG: Well, I keep busy, I read and make

little drawings. I even make little thank-you sketches of Mickey Mouse and

Donald Duck and Goofy and things like that now and then. I don’t have a dull

life.

DG:

Will you ever write a book about your career?

BG: [Laughs] Who knows? I may sometime, but right

now I have been challenged to make a bust of Obama, not because I want to

interfere with what is being done at Disney, but because I would like to

complete my cycle of sculpting all the presidents since Gerald Ford. I also

admire Obama a lot and I would like to do a bust of him. I won’t say it will be

the last thing like this I will do, but it takes a little more effort to do

these things as you get older. Especially when you’re ninety-one. I feel good

and I have the strength, but it would be much easier had I had my old studio and

all my tools available.

The full interview of Blaine Gibson is available in Didier's Walt's People Volume 13 which i strongly recommend as it include too many others great interviews with Roy E. Disney, X Atencio, Fess Parker, Don Iwerks, Bob Moore, Tony Baxter, Floyd Gottfredson and many more. Make sure to check the publisher website Theme Park Press HERE for more infos, including the table of contents and others excerpts.

Interview: copyright Didier Ghez. This interview was transcribed by Edward Mazzilli. Most of the questions for this interview were provided by Jim Korkis.

Pictures: copyright Disney