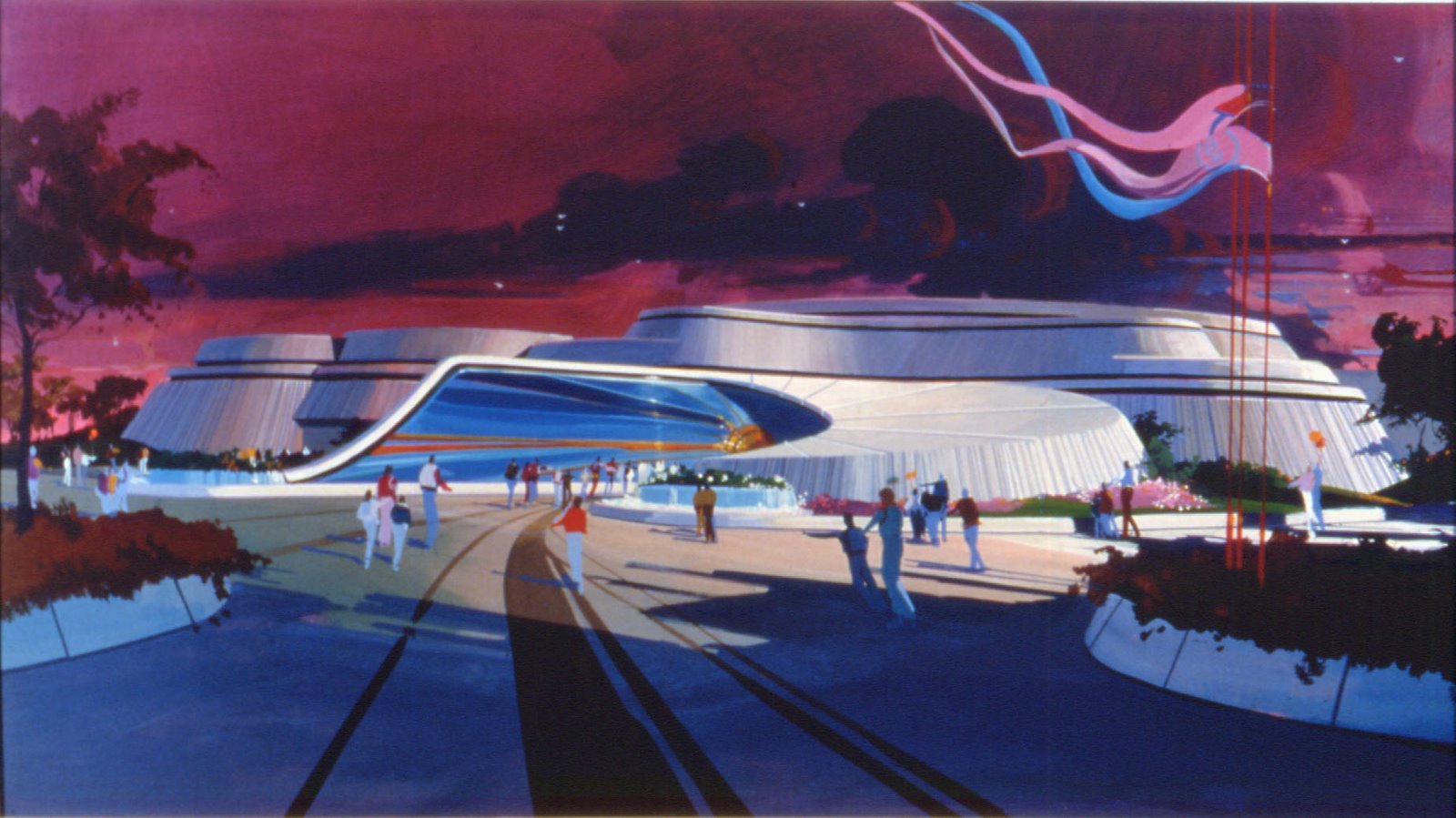

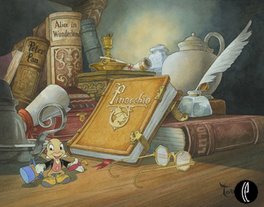

In this part two article about the "Epcot World Showcase Equatorial Africa Pavilion that never was" we will have a closer look at the "Heartbeat of Africa" show thanks to a great 2010 interview of Director and Cinematographer Jack Couffer coming from the Volume 12 of my friend Didier Ghez excellent book series "Walt's People" and the original Herb Ryman artwork for the show that you can see above, thanks to John Stanley Donaldson who is the author of a great book about Herb Ryman: "Warp and Weft".

If you've missed the part one of this article, it's better you read it first HERE.

According to Imagineer Ken Anderson original presentation: "The Heartbeat of Africa show will open as a standard 70mm projection on a section of the dome filling an area of 28' x 53' there are two themes to our show: the first is to present an image of what Africa is like today - the differences of its peoples, the contrasts of traditional with modern, an "african experience" that will give both insight and entertainment. The second theme is an exploration of the evolution of music which probably began, as man himself might have begun, in africa. Our title derives from the concept that everything has both visual as well as audible rhythms.

As the film progresses, the music will follow its historical development, beginning with the sounds of nature, then moving on to the imitation of those sounds by the original instruments - drum, rattle, bells, and flutes - voices singing and chanting give rhythm to work. the drum-beats and flute notes of the first music become more sophisticated as they are used to accompany ceremonial and dance. Then african music went out into the rest of the world where it influenced european and african music. finally, at the conclusion of our show we will discover that african music has gone full—circle to return to its source in thoroughly modern jazz.

As an outdoor jazz concert in a modern african city builds in excitement, occasional super—imposed laser images will begin to be seen, interpretations of the now—modern music, growing in importance until our film presentation has changed into a full—blown laser show as modern as the new african music that throbs through the dome. In this way, we will have led our audience, both in sight and sound, through the long evolution of modern music, and to have shown its african heritage."

The Heartbeat of Africa show would have had a fantastic pre show described by Ken Anderson, its creator, as "a Tiki Bird show only with talking drums":

"As the guests enter the salon to await the film show they are greeted by the sound of a full orchestral arrangement of traditional african instruments and voices in the "welcome ceremony." The waiting area will be the interior of a chief's house attractively decorated with colorful african masks and objects individually illuminated. Centrally located will be the circular preshow stage mounted on a dogon platform called a togu—na. Traditional african musical instruments - xylophone, the stringed cora, the mbira (or stomach piano), fifes, horns, flutes, bells and gourd rattles—-will be hung from the ceiling. After the opening "welcome" number there will be other arrangements featuring these instruments playing african theme music. Many african tribes have musical themes to represent nature's manifestations——the forest, rivers, mountains, rain, different bird and animal species, etc, these will be the themes we will use. Each will be identified as will the names of the various instruments. this section of the preshow in the waiting salon will last approximately nine minutes -slightly over one half of the total 17 minute time for the pre show."

"Then our hostess (an ethnic african) will appear spotlighted at center stage and begin the final 8 minute segment of the preshow. She will welcome the audience and inform them that the music and rhythm they have been listening to are the "heartbeat of africa" - the very core of african life. essential to this music around which life revolves are the african drums - like the drum family which she is about to introduce. These drums of various sizes and designs are arranged on the stage in a semicircle. as she introduces each one by its name, it is spot-lighted and responds with animation and a drum roll (each drum beat will appear as an impulse spark of light at the point of origin on the drumhead.)"

As for the "Dome" show itself, which was following this brilliant drums pre-show, here is the Ken Anderson presentation:

"The drumbeats have not been interrupted as we enter the fully illuminated theater. Then as guests have taken their seats and the lights dim, huge drums, appearing three dimensional as they seem to tumble overhead across the dark sky, sail away like asteroids in space, growing smaller as they reach a common vanishing point at the front center of the dome. out of the zone of disappearance something appears. It grows, pulsing with the drumbeats, and becomes a decorative visualization of the african continent; throbbing with the drumbeats until we feel they might be the very heartbeats of the earth. The continent grows and grows until africa fills the whole foreground of the dome; then as it continues to grow larger we are inside the land mass, zeroing in on the central part where a huge waterway divides the land - the river congo.

The drumbeats fade as another picture dissolves from the dome onto the film screen: the lush green treetops and winding rivers of an endless forest. Silence; then as we descend closer toward the trees, we begin to hear the sounds of nature, a hidden insect sawing from the leaves, a bird call, a monkey's screech, water's song. Down and down we soar, like a great bird of prey, until we are into the trees.

The scene changes to a large bird soaring through the forest. An unfamiliar sound-—odd percussive notes—— pick up the bird's rhythm as it slowly flaps to a landing on a vine—draped tree.

The camera moves toward the source of sound - behind the giant buttresses of a forest tree. out of the shadows of the roots, a figure steps into the sunlight - an old man, the griot an appealing-looking gentleman with wrinkled skin and a sparkle of humor in his eyes. This engaging personality who will become the leitmotiv of our film has a face and bearing warm with personality. On a strap held tightly under his left armpit, he carries an hour—glass shaped squeezedrum - the ancient talking drum of west africa. The griot indicates to us, the camera, that we should follow him: the old man has become our symbolic guide. When he addresses us, it is directly into the camera: like us, he is an insider, and he engagingly (and somewhat conspiratorially) takes us along under his wing.

Moving behind him, we enter the forest. we follow the old man, magically guided through a variety of locale. Sometimes we see as through his eyes: sometimes he is there on the trail before us as he leads, showing us the rhythm of nature - the beat of the herds of antelope pounding across the kenya plains, the giraffe in their nodding canter, the tempo of the hippos snorting spray in their pool.

With his drum, the wise old man imitates the natural rhythms, turning nature's sounds into man's music, showing us and telling us without words where his music comes from.

The griot is an acute observer of nature and he points out details which without his help would have gone unseen. The camera - our eyes goes on, stopping, seeing, moving again. the lens has totally assumed a subjective point of view and we move through a forest alive with creatures that must be sought out with the camera eye, vignettes of life that are only seen—-and their rhythms heard+—by the most experienced hunter. The formations of pelicans at nakuru in their choreographed fishing behavior, the fish eagle shouting its superb cry, a horde of multi—colored butterflies whose wings make a soft rhythmic patter as they flutter over a puddle, the thousands of pink flamingos that burst in a stunning crescendo of sound and color from a black lake.

Water ripples across the dome: it becomes a cataract. suddenly the spray is parted by the bow of a huge canoe. The chanting of strong men's voices bursts into the dome and we are with the powerful wagenia canoemen of zaire, transported as we are carried with them into the boiling rapids. Bursting with vitality and physical strength they stand tall at the long paddles of their canoes, twenty men to a craft, pulling together in exacting rhythmic strokes, chanting to help them in their great energy, pulling us through the rapids with exciting speed.

Their chant segues into the chant of the men of marsabit wells. Twenty men in loincloths cling to a scaffold of poles that descends deep into the earth to reach the water —- chanting to maintain a tempo of work. the men, muscles rippling in the dripping water, pass up the skin buckets hand over hand to the daylight where herds of thirsty borana camels and cattle stampede to plunge their noses into baked mud troughs.

In Mali, a group of drummers beat a tempo as singing men and women flailing sticks thresh dried millet from the stalks——we catch the eye of the old griot, nearly hidden behind the other drummers as he accompanies them with his drum. he gives us a grin and a wink—letting us know that he is still with us. Then on the beaches of Senegal, chanting as they pull their net, the seiners take up the tempo. A graceful pirogue is poled across the mirrored water of Casamance to the song of the boatmen near Sangha, women pound grain in tall mortars, one with a baby slung on her back, asleep, its little head lolling from side to side in rhythm with the work and song.

Then we are in the lively market at djenne, following behind a woman as she weaves her way through the colorful multitude. On her head she balances a stack of loaded egg trays three feet tall. She moves with graceful nonchalance, colliding with merchants, stopping abruptly to let running children race by at her toes and, somehow,incredibly the eggs perched so crazily on her head do not tumble. As she passes an overhanging balcony, the griot appears. He reaches down, plucks an egg from the top, gives us a conspiratorial grin, breaks the egg, throws back his head, and swallows it raw.

The lovely senoufo girls of the ngoro ceremony and the acrobatic boys of the leopard dance near korhogo, the twelve-foot-tall masksof the Dogon in mali dance to the ancient sound of drums, the wildly whirling dancer—drummers of the baoule, the tumbling of the Wakamba, people dancing across the wide breadth of the continent. In ivory coast the masked dances of the dan leap on tall stilts, while the knife dancers of danane challenge gravity and fate with their perilous dance as young boys are seemingly caught in mid—air on the sharp points of long knives. the dazzlingly painted Nuba of Sudan fill the screen with their suberb ritual.

Then, we are again following our old friend, the griot, through the forests of Kenya. what is that rumbling sound coming from the green wall ahead? We approach cautiously. a soft hissing sound, as of air being blown through a large hose, comes from behind the leafy screen - the muffled crack of a limb being broken, then a glint of mottled cream and white - ivory - and out of the leaves an enormous shadow materializes. Suddenly the forest parts and a huge elephant towers

threateningly above us. Its ears flare as wide as barn doors and its trunk goes up trying to zero in on our scent; its head goes back and with a heart - stopping trumpet, it charges. The rest of the herd follows in wild stampede, the bugles of many huge beaststhunder toward us.

Then they are gone and as the dust settles the old man resumes his soothing music - almost an irony now after the excitement of the elephants - and we find ourselves approaching an odd—looking vehicle manned by a friendly crew of grinning men.

The weather—beaten face of the driver is as craggy as the rock kopjis on the plains. we join them as with a shout they grab for handholds and the old truck leaps forward with surprising acceleration. It is one man's version of an off-road racer, its many dents and bruises the result of countless collisions with trees, boulders, and the sky, looking down on one of the most beautiful modern cities in the world.

Wild animals it pursues. we race out onto the plain and our purpose immediately becomes clear. We are aboard a game—catching vehicle, manned by the Kenya government capture and translocation unit, and the ride is the most hair—raising experience imaginable. flat—out on the tail of a herd of giraffe, we follow whereever they go, through gulleys, over ant hills, across rough grasslands. We plow through thickets of thorn bush without slackening speed, explosions of wicked thorns rat-tat-tatting against the windshield. We pull alongside a young giraffe and a man who seems to cling to the truck with his toes reaches out with a lasso on a pole and nooses the animal.

Then the giraffe is held by men in a different locale. It is released and gallops off to join its herd in new green pastures where they will be forever safe.

The griot grins knowingly as he watches the young giraffe canter off with his herd; then the old man turns and as our view widens, we realize that we are now in another place and time. We follow the griot through the crowded sidewalks of a modern city, and his drum takes up the new exciting rhythm of the bustling city of Dakar. Then other music blends with that of his drum-—modern jazz-—somewhere in that crowd ahead a band is playing.

The music continues, growing richer, and now we are high in the sky, looking down on one of the most beautiful modern cities in the world; tall buildings on a green finger of land-—the cap verde——point into the blue atlantic. In the heart of the city, surrounded by modern skyscrapers, is a wide mall - the place de l'independance - and as we descend toward it we see that it is jammed with thousands of people. The sound of the jazz concert grows louder and more exciting, people in the mall are dancing. closer, as we come down, we see the sengalese group called, jalam, dressed in traditional clothing, incorporating traditional african instruments into their exciting music.

Then we are on the mall, continuning the long move that was started out of the sky, moving now through the joyously dancing people, toward the old griot who is dancing and drumming with jalam, moving through the musicians, and our music has gone full- circle, out from its primal origins in africa and back again.

We continue to move, closer and closer until we zero in on the drum of our old griot. Closer and closer until only the drum head fills the frame, and then as his fingers strike the skin we begin to see eruptions we can only describe as visual sound-laser light effects, interpreting the music in visual images, colorful, growing stronger as we cut back to the entire group of jalam, and now each of the instruments is emitting visual musical images, erupting from the drumheads, horns, and strings, increasing in importance until they explode in color and motion and take over the whole dome above us. The music plays on, fuller and more exciting, but now dakar and the griot and jalam change from realistic to surreal, vibrating with vivid color as they play, an exciting phantasmogoria of exploding, melting, drifting african designs, dazzling in three dimensions,

Then the show has ended and the hostess who greeted us is saying good bye, interpreting for the talking drums: "Farewell, my friends, farewell. Go in peace. Until we meet again, farewell.""

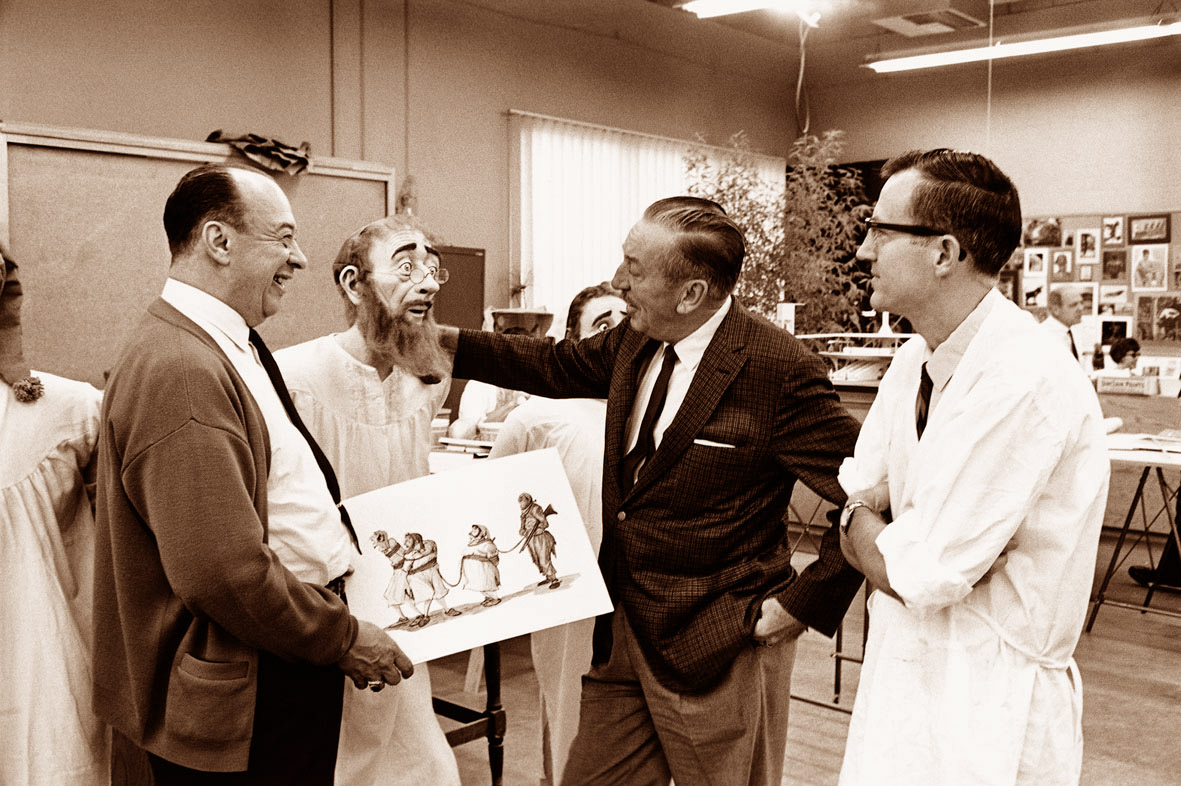

It surely would have been a great show, and now, here is the interview by Didier Ghez of Jack Couffer - picture above - who filmed the movies for the Africa pavilion and who was one of Disney's key naturalist-cinematographers on various "True-Life Adventures" and on many of the best "nature" movies that the studio produced for cinema and TV over the years. This is an excerpt from Jack Couffer full interview that you can find in Walt's People Volume 12 and Jack tell us more not only about his work on the project but also about why the Equatorial Africa pavilion was cancelled.

Didier Ghez:

How were you brought on to the African Pavilion project and when?

Jack Couffer: I was there pretty much from Day One until it

ended. Ken Anderson was the lead man. He knew I’d been living in Africa for

years, knew Africa, that I had made successful shows both for Disney and

elsewhere, and asked me.

DG:

Who was the creative team on the project besides yourself?

JC: Randy Bright was in charge of all EPCOT shows. He

was a chap who started his Disney career as a boat-driver-narrator on the

jungle ride at Disneyland and hung in there clear to the executive position he

held at WED. I answered to him. We all answered to Marty Sklar.

Ken Anderson was the first. He was a chum of Herb

Ryman and Herb was interested in Africa and sort of edged his way in so he

could do the design renderings. Ken did the buildings’ design and layout and Herb

painted the visualizations. There were just the three of us. Ken and I shared

an office at WED.

DG:

What can you tell us about the project itself?

JC: The original idea was that, like the other

pavilions, the Africa Pavilion would be paid for by the countries represented.

Morocco came in early, but it didn’t have the “Tarzan” flavor imagined by the

brass. Thus “Equatorial” was added to the idea. South Africa, wealthy and thus

the most obvious as a contributor (even though it was outside the geographic

limits, the country did have some traditional cultural interest). But it was in

the midst of apartheid times and troubles and was considered off-limits. A team

of Disney guys (and I don’t remember who they were if I ever knew) made an

unsuccessful tour of African countries to solicit partners. I don’t know who

they met with, but they failed to come up with any contributing countries. That

doesn’t surprise me, because we’re talking about mostly impoverished countries

run by governments with officials on the take. This all happened when the

Africa Pavilion was only an idea, before any development began.

Then the decision was made that, as a World Showcase

would be incomplete without Africa, Disney would fund the pavilion.

Ken came up with the idea for the big show which he

called The Heartbeat of Africa. Ken

and I researched the impressive history of African cultures, which is very

little known other than by students of the topic. Even educated American blacks

are pretty much ignorant of their sometimes (depending upon their tribal

origin) rich, ancient, and sophisticated African antecedents.

We decided that as human evolution began in Africa, we

could make the assumption that musical evolution also began there. And as the

drum is the most primitive musical instrument, we could begin with that. (Even

chimps “drum,” although we didn’t go back that far in our historical study.) So

the development of music from its roots to present day was our theme.

We discovered that in traditional African societies—and

there are hundreds (maybe thousands) of very distinct tribal societies—one

nearly universal trait was the importance of music. Music plays a vital role in

nearly every social event—religious ceremonial, births, death and mourning,

field work, sports, wrestling, paddling, the list could be long. All of these

activities were wonderfully visual and exciting audio experiences that lent

themselves to film.

I made my first across-Africa tour, researching the

places where I could shoot the kind of stuff we were after. Along the way, I

was instructed to make pitches for contributing funds, and so met with upper-level

government people—presidents and ministers, in Senegal,

The Gambia, Ivory Coast, Mali, Zaire, Guinea, Ghana, Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania,

and Sudan. This was necessary, anyway, as I also had to be assured of obtaining

the necessary permits and government cooperation. The Disney name opened doors

that would otherwise be hard to crack. And my first meetings in each country

visited were usually arranged by the USA Embassy in that country. I met with

titles such as Minister of Information, Minister of Arts and Culture, or

Minister of Tourism. I met the people who the first guys should have

approached, but didn’t.

I never met any African government official who knew

of the project or had been approached by the first team. My conclusion was that

the Disney guys had a good time visiting tourist spots, but not attending to

the business they’d been hired for. Or maybe they just didn’t know Africa or

how to get around in Africa, which does take a bit of getting used to.

Well, I can’t say that it mattered. I didn’t raise any

pavilion money, either. But I did get tons of goodwill and the cooperation

without which it would have been impossible to film the things I was after.

Later the President of Guinea (a country which does

have the money) came to WED with his Finance Minister and met with Marty, but I

was out of that loop by then and don’t know what took place. In any case,

nothing materialized.

For EPCOT everything had to be grand in scale. IMAX

and 3-D shows already were in use in three shows. I had to come up with something

different. See my book (The Lion and the

Giraffe) for a description of the system I dreamed up.

Note: In The Lion and the Giraffe, Jack Couffer wrote: “I imagined a show even grander than IMAX: three IMAX-sized screens, side by side, each with an image of the same action but shot from different points of view.

“Three huge screens, each with different images, all running simultaneously, might seem difficult for an audience to absorb. One can’t see everything at once on so large a scale, just as one doesn’t see a lot peripherally in real life. But one’s eyes tend to rove—or be directed—and it’s easy to gather an impressionistic feeling of all that’s happening.

“The main center of action was the middle screen, but the eye could be randomly directed […] shifting from middle to one side screen or the other. With this dazzle of imaging, editing, and sound, the format alone—the three huge screens—would be exciting.”

I made three tours across Equatorial Africa. The first

was to find and select the different traditional events I wanted to film. I was

accompanied by Sieuwke Bisleti who spoke French. Important, as most of West

Africa (where there is still lots of traditional life) is French-speaking. She

had a way and personality that quickly charmed the Ministers and although we

never got the funding, we did get wide-open doors and access to everything we

asked for. Sieuwke and I went deep into the hinterlands to find traditional

culture as untouched by modernity as it still exists in remote places to this

day.

We returned to Burbank and I finessed the script to

incorporate my discoveries. Then Sieuwke and Production Manager Eva Monley and

I made a second trip and arranged for the people, places, and times for the

shoots.

On the shoot, my crew consisted of Steadicam operator

Steven StJohn; gaffer Larry Prinz; sound recordist Michael Evjie; accountant

Mac Meltzer; assistant camera Michael Couffer; gofer Michael Fields; Sieuwke,

Eva, and myself.

The shoot was about three months long. Then Norman

“Stormy” Palmer set up three linked editing machines side by side, and I sat

beside him in one of the Studio editing rooms and we cut the picture.

DG:

How far along was the project developed before it was canceled?

JC: From the time it was put into play, the Africa

Pavilion was not planned to be ready on opening day. We had a late start due to

the fumble over African funding. Thus our pavilion was to open exactly one year

after the official opening day of EPCOT.

There was to be the main show, Heartbeat of Africa, in the largest building. It would also house a

collection of African musical instruments. There were to be hosts and/or

hostesses who would entertain those waiting in line for the twenty-minute

change-over to enter the Heartbeat

show.

Another building would house a museum-like exhibition

showing the surprisingly advanced cultural aspects of different African tribes

at the time of European discovery. There was to be a gift shop stocked with

everything from African folk art to expensive old wood carving and treasures of

brass and ceramics. And there was to be a restaurant that served, of course,

different African meals.

The

Heartbeat of Africa was finished and had three

screenings (one for invited guests) on a soundstage on the Disney lot where it

was applauded enthusiastically.

The Tree House film was shot, a miniature model tree

house was built, and a full-scale model was roughed out.

In the meanwhile, the death of Walt, the competition

between Roy Jr and Ron Miller for top spot, then the successful opening of

EPCOT all spelled doom for the Africa Pavilion. The land for the pavilion had

been reserved and signposted with appropriate “coming attraction” signs. A few

props were on the spot (a thirty-feet long Senegalese seagoing canoe that I’d

bought and had shipped from Senegal was on the lakeside). Sites for the

buildings were staked out, but construction had not begun.

The general attitude was, “We’ve only spent a couple

of million dollars on developing this, EPCOT is a thriving success without it,

so why spend a lot more when nobody will miss it? Do we really need a costly

African Pavilion?”

I think a lot of the fascination with this project is

in how close it came to reality. One gets the feeling that, conceptually, it

was almost completely ready to go. The design seemed fairly fixed. I've just

long wondered if any of the filming was actually done, and how/when/why the

project was officially canceled.

DG:

Any other stories you have not told about the African Pavillion and the artists

who worked on that project?

JC: Yes. This is the way Herb Ryman got to know and become

friends with Alex Haley... All of this happened at the time when the Studio

employed no blacks in the higher echelons of management. In prior years there

had been an incident at Disneyland with the cowboys and Indians section

(Frontierland) that had created a lot of press. A group of Indians (excuse me—Native

Americans) had various objections, I've forgotten the specifics, but it got

substantial press and made Disney look bad.

So one of the V.P.s.—I

seem to remember that it was Harper Goff, but can’t be sure—was super sensitive about minority issues. And blacks, in particular,

were a dangerous mystery to him. So he questioned the suitability of my movie

and wanted to get some black input.

Marty Sklar called the UCLA black history department

and arranged for a half dozen students to look at the film and comment.

Couldn't have been a worst move. These young guys came with a chip on their

shoulders. The theme of the film was the development of music in Africa (where

it all began), and it covered a lot of traditional music in traditional

settings. The gist of the objections that came from these kids was their

embarrassment that some modern Africans look and behave the way they do. I

wasn’t showing the Africa of today—suits and skyscrapers—but dwelt on Africans

who still live in the traditional way. The film was about history, after all,

and African blacks, unlike African-American blacks, are of a different kind.

All blacks who saw the film or knew the concept—and there were many—loved it.

These UCLA guys missed the whole point of the Africa Pavilion, which was

directed at showing the rich cultural history of the continent and the film

greatly enhanced that point of view.

Here is an example of a UCLA kid’s reaction: Once when

I cut to a beautiful African child watching a traditional event, a remark from

one of the students was, "Oh, my God, there it is—the

pickaninny shot." I laid into him after the screening and Marty was

uncomfortable with my irritation.

Marty was uneasy after this session. I agonized as to

who I could get to counter the student agitator remarks, someone who would make

an impression on the Disney folks, and I settled on Alex Haley. I got his

number somehow and called him out of the blue. He wasn't connected with Disney

in any way. He came, saw the film, loved it, and became my champion. He got

support from Loretta King and others in the important African-American

community. He made such an impression on the Disney folks that he was invited

to join the Board of Directors. He told me they merely wanted him on the board

as a "token black" and declined.

I don’t think he was ever officially a WED employee or

on the payroll.

I considered writing about this incident in my book,

but it went out the window with a lot of other good stuff.

Both Herbie and Ken Anderson, but especially Herb, became

good friends of Alex. And of course, I thought of him as a friend. But I

believe Herbie was the closest.

Herb painted a large oil portrait of Alex which was

still in his house when I last saw Herb shortly before his death.

There was one potentially touchy detail for which I

wanted to get Alex’s input before I screened the movie for the Disney brass. I

had shot a lot of dance and ceremonial material in remote areas where the

tribal people still lived in their traditional way. One sequence, the Poro

ceremony in northern Ivory Coast, was a favorite. A dozen musicians played

flutes, drums, portable xylophones, and other percussion instruments for which

I only heard the local names. They were led by a grotesquely masked and

costumed figure who repeatedly cracked a long whip with explosive reports. A

dancing chorus of twenty bare-breasted girls wove through the players in a

snake-like column shaking pom-poms with rattles. All was filmed at night in the

light of open fires. It was wild, spectacular, and exciting, one of my favorite

pieces—but what would Disney folks (Disney being what Disney is—or was) think

of bare-breasted girls?

Alex Haley loved it and found no reason to edit the

boobs. I agreed and so did Ken Anderson. I never heard any criticism from the

brass. Everyone seemed to like it. Perhaps their approval was a bit daring for

Disney, and I was pleased with their pluck.

Technical note: I shot this show with two cameras in

35mm (myself and Steve St John operating). 70mm cameras, although they are used

for IMAX shows, were too bulky at this time to ship and use with a small crew

all over Africa. We did a lot of experimentation with 35 mm projection on the

big screens. Because of a slight jitter between frames of 35 mm at 24 frames

per second, we modified our cameras to shoot (and the projectors to project) at

40 frames per second. This smoothed out the jitter and with the sharpest

anamorphic lenses available at the time (Technoscope—a British company), the

result was nearly indistinguishable from 70 mm.

I’ve got some regrets about this project. I spent a

year on the film, researching, location scouting, writing, shooting, and

editing. I was disappointed that it was never shown in its proper venue. I was

proud of this film—for its difference, its enjoyment and quality. Also, some of

the ethnographic things may never be filmed again. Surely they would have been

of interest to some anthropologists and musicologists. Even if the footage has

been saved (and I doubt that it has been), it would be difficult to screen

because of the 40 fps. Also because as it was shot so specifically for three

screens, that would make viewing difficult. Still, the center screen pretty

much told the story and carried the show and that alone might have been of

value to anthropologists.

And it's with this interview of Jack Couffer that ends this two-parts article about the Epcot World Showcase Equatorial Africa Pavilion that never was, which i hope provided you the answers to the many questions that Disney fans could have about this legendary project.

You can find the full interview of Jack Couffer - in which he talks about his long career of naturalist-cinematographers for Disney's "True-Life Adventures" and "nature" movies in Walt's People Volume 12 that you can order on Amazon HERE.

Artwork: copyright Disney

No comments:

Post a Comment