I've got for you today a fantastic interview of legendary WDI Imagineer Tony Baxter. This interview was originally published on ThemeGo Blog by Yariv Padva who interviewed Tony and kindly allowed me to post it on D&M. ThemeGo is a great place to share experiences and read reviews about every element of a theme park vacation including attractions, shows and more. Check them out at: http://www.themego.com

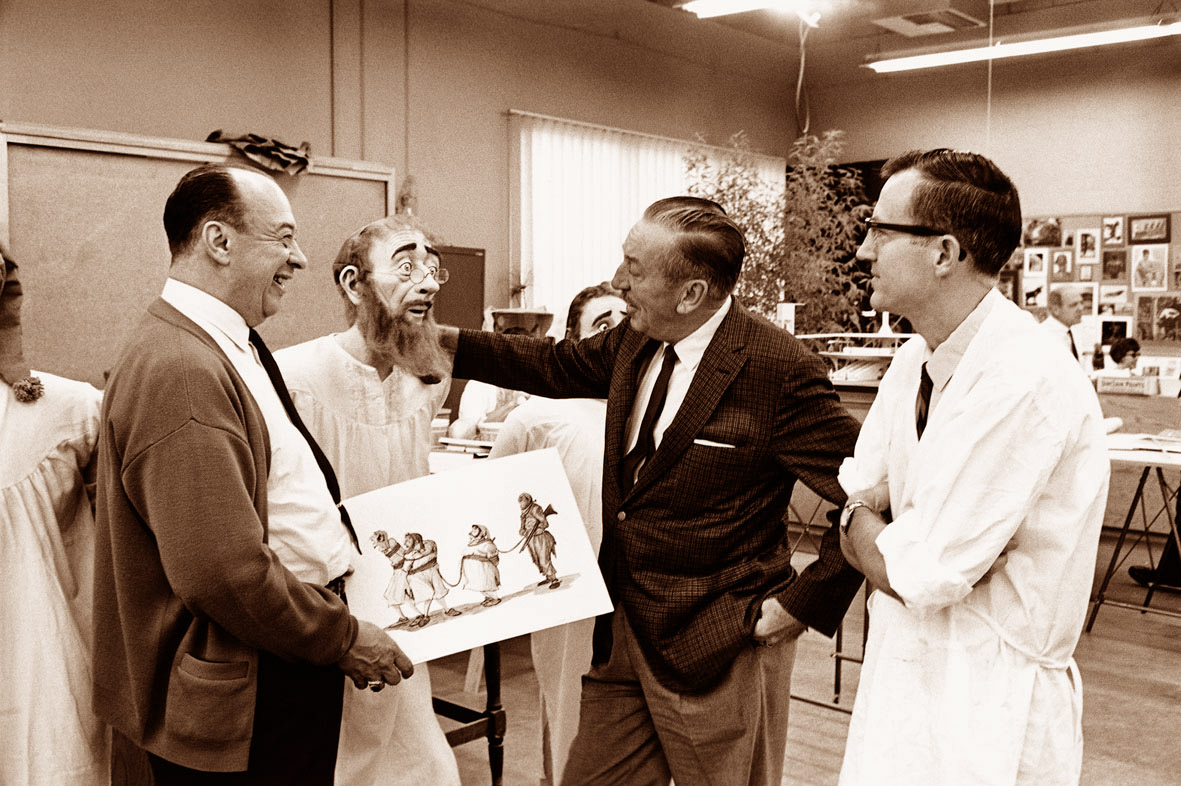

Tony Baxter, the former SVP of Creative Development for Walt Disney Imagineering, hardly needs any introduction. Tony was responsible for attractions such as: Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, Splash Mountain, Indiana Jones amongst others that have entertained and delighted theme park goers and Disney fans for decades. Join us for this first part of the interview as we explore exciting and thought provoking thoughts about the past, present and future of theme parks, imagineering and more!

Yariv Padva:

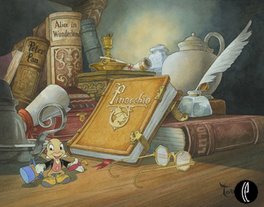

Thank you very much for this interview and congratulations on the new book: Tony Baxter: First of the Second Generation of Walt Disney Imagineers. I’ve read it, and I think it’s a terrific book, and I think you can learn a lot about your philosophy and just that unbelievable life story and be inspired by that.

Tony Baxter:

Well, good. You’re one of the first people I’ve talked to that’s actually gotten a copy of it.

Yariv Padva:

Yeah, it’s brand new. So, how did the idea for the book come about and your connection with Tim?

Tony Baxter:

Tim has been writing for the themed entertainment industry for years and I knew him when he wrote long, long ago for an in-park magazine or something, and I’d done a couple of articles for him. Tim called me and said that he wanted to write a sequel to a book that he did on legends of themed entertainment. So, he was initially going to include me in that as one chapter. Then, as we started talking and it got more involved, he said, “You know, I’m now thinking maybe I’ll do this as a separate book, a small book, rather than just one chapter in a larger book of eight or nine different people. I think I’m going to approach what I do in the future that way. Yours will be one of the first ones.” So, that was how it happened. So it just grew out of being one of, say, twelve people that would be featured in a second volume of his legend book. I’m very happy that it turned out that way.

Yariv Padva:

Yeah, I’m very happy as well, because I was able to hear about all of these amazing stories. So, it’s really inspiring. Thank you for that. In recent years, Disney’s own IP (Intellectual Property) has grown so much. Now that Pixar and Marvel are part of that IP, how do you identify which IP can be turned into a good ride? Do you think it would be best to go from an idea for an attraction and then think which IP can be the best fit, or the other way around?

Tony Baxter:

I’ve done it both ways. Journey into Imagination was something where we had a subject that was not at all identified with an IP. As I told in the book, the name Figment became very important to creating IP. So, once we identified the name of Figment, we built this character that’s really become amazing to me, because you can Google the word ‘figment’ and see that character comes up. We don’t own that word, and yet it has become the visual of that particular word. So, that’s one side of it. I think Thunder falls into that side of it, but Star Wars and Indiana Jones are on the other side of it. I love both of those films, and I think what it boils down to on IP, and this is my personal feeling, not WDI’s or something. I think I look for, if it’s existing IP, it has to have an emotional connection with the audience.

On Indiana Jones and Star Wars, I think that the thing that people sort of look over when they say, “Oh, Star Wars is spaceships and battles and all that exciting stuff;” It’s also emotionally a story about human beings and their feelings, and I think that’s true with Indiana Jones, that he is a great personality as well as having wild, crazy adventures. He was just so well-defined and I think it’s true of the best Disney movies. If you go back and you think of the animated films, we really care about each one of the princes or princesses, whatever it might be, if you’re very involved in their lives.

I think the danger of IP that’s already existing is if you link with something where nobody really cares about the characters, it’s more just about the fireworks or the battles or the special effects and CG and monsters and so forth. I think that’s dangerous, because really the value of IP is caring about the characters that are involved in this. So, whenever I’ve been dealing with IP that already exists, I make sure that there is really a strong affinity by the audience for those characters that live in that world. The fact that they go to magical places or they have amazing confrontations with creatures and whatnot, that’s secondary to how wonderful they are as characters. I think that would be my decision on whether or not I would work on IP. I think a good example, not Disney, is the Harry Potter series. It’s a great sense of IP, because every single person that read the books or saw the movies cares about Ron and Hermione and Harry. They identify with those three kids going to this amazing school. Sure, all the creatures and everything are interesting, but the reason that works is because you care so much about those people.

Yariv Padva:

If someone would like to become an Imagineer today, what kind of education will give him or her the best set of tools to realize that dream?

Tony Baxter:

Everybody asks me that and it’s very, very different from what I grew up with in terms of technical skills, because I grew up using paintbrushes and pencils as my tools to draw. Of course, it’s kind of a cliché to say, “Well, you’ve got to learn to be creative on the computer.” That’s part of it, but what I just talked to you about; really being sensitive to understanding the emotional side of when something moves you and you can feel it and you get goose bumps if it’s spectacular. You want to cry when somebody is hurt and all of these things. You’ve really got to be in touch with that, and a lot of people aren’t. They learn all the technology; they learn all the skills; they’re very good artists and all that stuff, but they don’t know how and when those things that move people emotionally are working, because one of the things I always say, “You’ve got to discipline yourself to think about when you’re designing. Don’t design for the first time you’re going to go on a ride or see a movie. Design for the 20thtime you’re going to see it and force yourself to say, “I’ve seen this 19 times already. Why am I waiting in line at Disneyland to go on the Peter Pan ride for the 20th time? I’m waiting a half an hour to get on that boat and do it again. Why?” I can tell you, it’s always about the emotion of it. It’s not necessarily about what you’re going to see on the floor or down below you or anything like that. It’s the fact that there’s something that’s aspirational and it’s worth it to you to get to have that feeling again, that emotional experience.

So, teaching that and learning that isn’t that much different today from it was when I was going through it, but I don’t think it’s taught in a class. So, there’s nowhere you get that. It’s part of your understanding and the way you look at the world or it’s not. I work with people here that I know have it, and immediately I can read it when I look at their drawings or whatever. I can see that it’s in there. Then, other people that are great illustrators who we have here, and you use them because you need the work illustrated, but they don’t know how to bring out the emotional sense of it. There’s jobs that are roles in both sides of that. If you want to be leading or creating new worlds, then you’re going to have to know how to make that work, because if people only want to see a movie once, or they only want to go on an attraction one time, especially where you build it out of concrete, it costs a lot of money. It really depends on every time you go to a park, you want to go and revisit that, because it emotionally stirs you and you like that feeling of being moved emotionally. I don’t know where you go to school to learn that. It’s just something that has to be a part of your soul. Then, learning all the techniques and technologies, and they evolve and change with time, that’s important too, but if you don’t have the other, you’re going to be limited or handicapped.

Yariv Padva:

How do you think rides and theme parks might change with regards to connectivity, social video games, and everything that’s going on with the new generation?

Tony Baxter:

Well, that’s a crystal ball question. If I had the answer to that, I’d be rich. Here’s the thing. Things that could last for 20 and 30 years in the past, I don’t think you’ll have that luck with things in the future. For instance, I remember when there’s a modern house at Disneyland in the 50s. They told you in the kitchen of that house that we were going to have microwave ovens that cook turkeys in 15 minutes. I remember, for 20 years that was a miracle that never happened. It never happened. You’d go in again; ’58, ’59, ’60, ’61, ’62, and they’d still tell you, “Someday you’re going to cook a turkey in 15 minutes.” Then finally it happened and what happens now is, you go out and you buy a high definition television and a year later there’s the Super 4K resolution television and you throw away what you had before as being obsolete. So, I think that’s true of everything that we do, and that’s why I say it’s really important that the emotional thing works. You take an old movie like The Wizard of Oz from MGM or Disney’s Snow White. Those are technologically archaic. They’re basic, using tools that aren’t even used even anymore to make both of those movies, but they still resonate with new audiences today because they’re more about the emotions of a little girl or a princess being thrown into a very dire set of circumstances, and we want them to live.

We want them to succeed so badly that that journey of them reaching a happy ending is really fun to go back and visit over and over again. So, there again, like you said, for me, when we did the attraction Star Tours back in 1987, it was really tempting to just push that out really quick and maybe make it a runaway ski ride or something where you’re skiing down the Alps or something, or you’re in a truck that’s out of control or something like that, but we knew that very quickly other people would copy that ride and they’d be everywhere. If we didn’t attach that spectacular new ride system with something that was emotional, it would be dead in two years. I think every other simulator that did do those kinds of things, where you were just on an out-of-control thing or dinosaurs were chasing you or whatever; those are all gone. They’re all gone, because people did it; they did it again, and they were bored with it. The reason Star Tours is still there is because everybody that fell in love with those movies wants that chance to once again reenter that world. I remember the line I put in the first one was, Rex, our pilot said, “I’ve always wanted to do this.” Literally every single person riding that is thinking the same thing; when they saw that first movie how they really wanted to make that approach to the trench of the Death Star and drop the bomb. So, putting those things out there doesn’t guarantee that it won’t go obsolete, but it certainly gives you a chance at people going back to something that’s now become commonplace but is still emotionally strong and still works on that plane.

Yariv Padva:

Yeah. Connected to the other question, what challenges do you think exists now when designing an attraction, considering how the young generations attention span is shortened? (using mobile phones…)

Tony Baxter:

A good example of what doesn’t work anymore; we had the first 3-D 70 mm film in Epcot in 1982 with Magic Journeys and then we did Captain EO. Those films would last for maybe 10 years in the parks before you’d need to put in a new show, but now that every movie pretty much comes out in IMAX and 3-D and it’s in the theater for a month, or two weeks, and then it’s gone. That’s how people consume films now. Back in the earlier days, a big, what they call roadshow movie would come out, like The Sound of Music would come out and would play for two years in one theater. You buy special tickets to go see it and that was the way it worked. Now, we’re in the shortened attention span. So, a movie like, this summer, Jurassic World was a great film, comes out. Everybody loves it, and a month later you can’t find in anymore, because it’s done. It’ll be on Blu-Ray. So, I think the attractions are the same way. So, we have 3-D theaters in all our parks. What we’ve had to do now is find a way to use them to create short-term experiences that get you all excited for something that’s coming. Right now, we have a 10-minute presentation of all the exciting moments from the Star Wars films and then a little bit of a peek at the new film. Then we add in-theater effects. So, the seats bounce and there’s flashes of laser lights and stuff that give it more 4-D experience. As soon as that movie comes out in 15 days or whatever, that’ll be over with and we have to then have something new. So, I think those kind of experiences like 3-D 70 mm or IMAX digital, those are no longer valid things you can do in a theme park, because they’re too much a part of the real world.

Everybody has those kind of theaters in their own hometowns. They’re not going to pay money to go to a theme park to get the same thing. So, you have to move on to whatever the next kind of thing is and for the time being, in the case of those theaters, we can use these short-terms films that give you a peek and people are excited to see five, ten minutes of something like Tomorrowland. So, we ran that at Disneyland, and I was so excited by the little short film that I was kind of disappointed when I saw the whole film. It was so good. The short, for me, was so good. It showed you all the really great parts of it. So, it becomes harder on other attractions. So, what do they offer you that sort of protects their obsolescence? That’s why I keep going back to Peter Pan. Peter Pan is such an aspirational thing. I don’t think, since children had bedrooms, which goes back to cave days or whatever, that thought of rising up out of your bed and flying out the window, soaring away at night; that’s never going to go away. That’s a dream thing that is as relevant today as it was 40 years ago.

When you look at the rather antique, painted black light remnant on the floor, or the optic fiber stars, it doesn’t really matter that we can do it better today, because it’s so dream-like. It’s something that you wish for, and you’re willing to wait in line, even in this day and age, to have that experience again. So, before you jump in and try to do a project, just because you have a new technology or you have a new ride, vehicle, or something like that, it’s really dangerous. You really need to stop and say, “Once everybody knows how that works and they’ve experienced the gimmick, or they’ve seen the new illusion, then what is it that this attraction offers you emotionally that is going to ensure that you want to go on it over and over again? So, it’s a little bit the same answer that I gave you on the last one, but I go that route because I think that’s the important thing that guards against building something elaborate that then nobody is interested in a year from now.

Yariv Padva:

In recent years, the gap between the theme parks and the amusement parks seem to have blurred a bit. Amusement parks start to offer high-quality dark rides. For example, Justice Leagues at Six Flags, and theme parks offer more thrilling rides that cater to a more mature target audience. Do you see this transition happening or do you think that the storytelling element in theme parks will set them apart forever?

Tony Baxter:

Well, there’s a danger on this thing that would be hard to argue. So, again, I have to say this is my opinion.

Yariv Padva:

Of course.

Tony Baxter:

We had a tremendous amount of guests at Disneyland here in California that really loved California Screamin’, and there is no screaming on it whatsoever. It looks like a wooden roller coaster, but it’s a steel coaster. If you ask a 12-year old, “What’s your favorite ride out here?” they might say, “Not Pirates of the Caribbean, not Indiana Jones, not Star Wars, but California Screamin’.” The thing that I think distinguishes what a theme park does, and yes it’s expensive, but by going the theme route, and I don’t mean just putting up plastic sign on something and saying “This is the Pac-Mac roller coaster.” I mean really going all-out and making it an experience where you go to a world that you couldn’t have visited without being in a Disney park or a Universal park or whatever. I think that guarantees you a sense of a different audience. I see people all the time worried about whether they should go on Splash Mountain or not. They look at that hill and they go, “Oh, I’m so afraid of drops like that. I don’t know if can ride it or not,” but they also know that it’s got a fabulous Disney storytelling element in there.

So, they challenge themselves to go on it. They go on it, and of course they live and it wasn’t as bad as they thought it was going to be, and they’re very proud after they come off. They go, “Wow. I did Splash Mountain and it was so exciting. We saw this and the music was great,” and all that stuff. Whereas, if you think about the other side of that, that same person was standing looking at California Screamin’, they can see there’s nothing emotional or intellectual about the ride. It’s just going to go up and down and be scary. So, they make a determination not to go on it. There’s no reason I need to go on it. I can see it all from here, so let the kids do it, but we’ll stay here and eat some popcorn while we wait. So, I think the defining factor, you look at a park like here in Southern California, Six Flags Magic Mountain, they do two million a year, and Disney does something like almost eight times that, you know?

Yariv Padva:

Right.

Tony Baxter:

I think that’s that difference, because everybody that goes on roller coasters; that’s the two million that go. The people that want more, and might allow themselves to be tempted to going on a Splash mountain is that they know it’s going to be scary, but they’re going to get that Disney quality reward, will challenge themselves to do something that’s a little more than they normally do because of the promise that they’re going to get an amazing adventure from going through this thing emotionally. I think, there again, yes you can be successful by doing that, but I think you’ve really limited your audience now to people that are die-hard coaster freaks or thrill-seekers, rather than really reaching out and challenging the entire broad audience to see what it is you’ve put into this amazing thing.

Yariv Padva:

When designing a theme park, how to you go about thinking in terms of making one coherent storytelling element using retail space, dining areas, and attractions? Can you give an example from Disneyland Paris?

Tony Baxter:

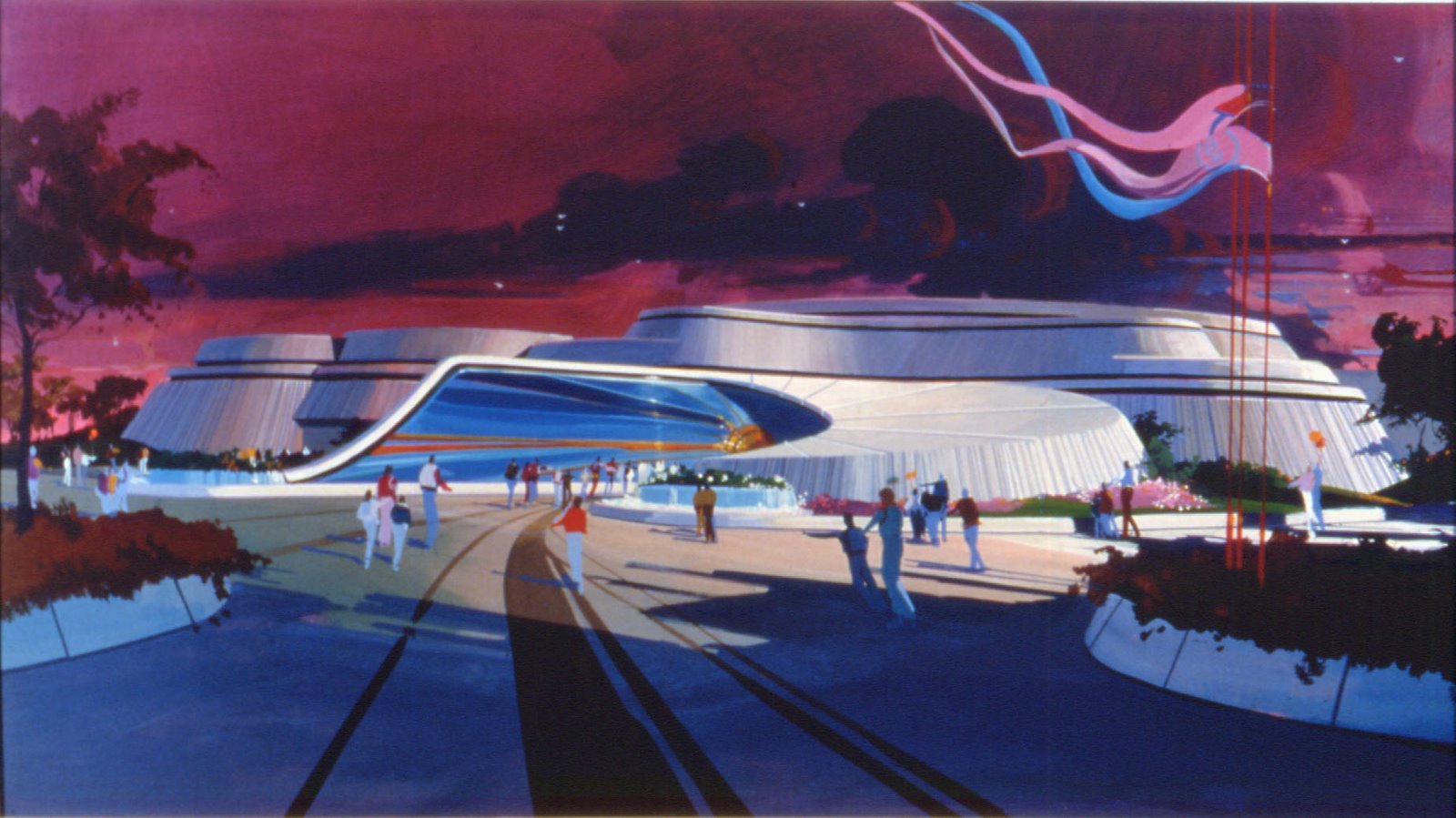

Disneyland Paris? Well, I felt we did everything right in Disneyland Paris. Of course, I’m prejudiced, but let’s say Frontier Land and Adventure Land. Both of those Lands are very purified. So, Frontier Land isn’t the all of the American West. It’s not the Kentucky hills and it’s not Alaska and it’s not up in Washington. It’s really just the Southwest; Monument Valley, the canyons, the Rio Grande River. So, it’s very strongly given a specific look. Now, I think that was more because we were in Europe, where there’s, I think, more of a perception of the West looking like that. Whereas here in California, we have the Mississippi, we have the Southwest, we have the Southwestern; we have Kentucky. We have all of these things going on and Americans are kind of comfortable with that, because they know our country has a lot of different environments going on, but I think we were really successful in going into an audience that has the desire to see an image that they’ve created in their minds from a lot of things. It’s from the many Western films that John Ford did with John Wayne. It’s form the Marlboro Man cigarette ads. It’s from a lot of things that have come through the popular culture to Europe about what the West looks like, and it’s a very distinctly different environment from the lush green world of Europe. It’s a very dry and desert-y place.

So, that works really well. If you go outside our gate and down to the Martin River, there’s swans and there’s beautiful weeping willow trees and all of this. It’s very romantically genteel. So, having this rugged, dry Frontier Land where the gardeners are working hard to keep it dry as our gardeners in California try to keep it green, because here it’s hiding the Santa Ana Freeway and it’s dry. It’s hot in Southern California. Then you get into Disneyland and the river is all lush and green and beautiful and all that. So, it provides a contrast here to what we have in our normal world. So, I think that works in California, but I think that the purity of all the shops, all the restaurants, even the haunted mansion, which in California is kind of Southern, like the Grand Old South. It’s like a plantation and it’s more like a Gothic European Manor, but in Europe it looks like the quintessential ghost house in a ghost town. So, everything in that Frontier Land arc of shops is working to tell one story, and by putting Big Thunder in the middle of it, you can’t get away from the energy of the trains and the kinetics that are the focal point of that. So, whether you’re on a mansion end or over by the barbeque, you’re constantly aware of that high energy, Western ruggedness going on in the middle. So, I thought that was very successful.

In Adventure Land, we did a similar thing, focusing through Arabian Nights, which is, I think more well-accepted in Europe as an exotic locale than it is in the United States. In the United States, the jungle is the only way we think of the Adventure Land thing. Over there, with stories like Babar the Elephant and whatnot that are part of the culture, we broadened that Land out to include not just that gateway with the Sinbad story, 101 Nights and all of that and Aladdin. Then, focusing on an island, that in California, is Tom Sawyer Island. That’s an American story written by Mark Twain. Over there, we created Adventure Island, which was about pirates and tree houses and exotic realms, and shipwrecks and coves and things like that. So, that one’s a universal fantasy of going away to some tropical island with treasures and whatnot. It seemed like that would allow us to do the same exact interactive things for children to go across bridges and stuff, the same thing we do in California with Tom Sawyer. We did it there with Adventure Island, but it’s a theme that’s more universal than just the kids along the Mississippi river in America, which is very focusing on culture. So, I think that worked really well. Then, as it turned out, with Disney ramping up the whole word ‘Pirates’ through the movies and whatnot, we were very lucky to have done that and now have a whole focal point of the park based on this very successful film franchise. So, that was luck that we didn’t plan. That was just something that happened, but I do feel that the whole Adventure Land over there works quite well.

We made a conscious decision to not do the jungle cruise in Adventure Land, because it had been done at Phantasialand and several other parks and even if ours was better, it would be considered to be a copy of something that the audience that was aware of already existing. They’d go, “Oh, this is just like the thing in Phantasialand. This has been open for 10 years.” We didn’t want to go that route. Also, the Jungle Cruise is very heavy on dialogue, and with five commonly spoke languages, we had to be what I called more visual in telling stories than in literary storytelling. So, the Haunted Mansion looks haunted. It doesn’t look haunted in California. Adventure Island looks like an adventurous place. Tom Sawyer Island doesn’t. So, the pirate ship is anchored right out in front of the Pirates of the Caribbean, so people that don’t speak the language can look at it visually and say, “That must be where the pirates are, because there’s a pirate ship and so forth.” So, we were consciously trying to use visual cues to tell our stories so we wouldn’t exclude anybody that might be a visitor from enjoying the park to the full.

What was it like working with George Lucas? What makes an animatronic character unique? To find out, jump to ThemeGo to read the part two of this interview!

You can find the great and not-to-be-missed Tony Baxter biography by Tim O'Brien on Amazon HERE and even in Kindle format for immediate download - and read! - on a Kindle, iPad, or any tablet device- with the amazon Kindle App - and for $11.81 only! Pictures: copyright Disney, ThemeGo

No comments:

Post a Comment